“The Perfect Mark,” by Melodie Campbell, is about greed. In my experience, raw greed is hard to come by: There’s always something else mixed in. In this delicious little crime story, however, greed is at its maximum level and completely focused — and the result is as dysfunctional as one could hope for.

A special congratulations are in order to Melodie, by the way: “The Perfect Mark” won third prize in the Bony Pete short story contest at the Bloody Words (Crime Writers of Canada) conference in Victoria, shortly before our date of publication.

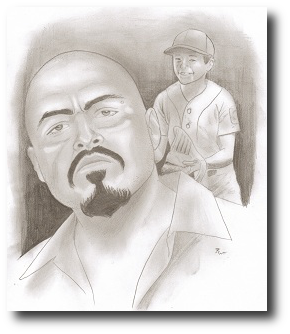

Kenyon Ledford’s “The Baseball Glove” is almost the opposite. There’s a surface of greed, of fear, of primal and animalistic emotion; but the real story is in the deeper feelings and motivations of its characters. This mainstream piece is pregnant with ideas about the lives that came before and after this scene.

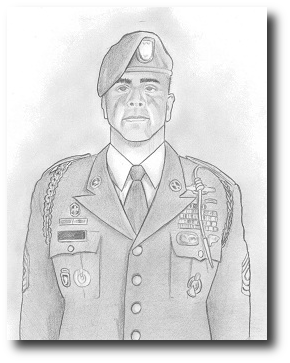

Our third new story, “A Purple Heart,” strikes a chord that’s difficult to describe. I could lightly relate it to clichés like “watch what you wish for,” but it runs deeper than that. Using a science-fiction premise, Craig DeLancey gives us a vivid sense that sometimes, the only thing worse than a terrible longing is its terrible fulfillment.

Normally, when organizing stories for an issue, I place a more serious story between two lighter-hearted ones, like a triptych or a sonata. In this case, the more natural fit seemed to be going from less serious to more. (These are descriptions of mood, by the way, not judgments of power or depth.)

Our Classic Flashes this month lighten the tone somewhat. I went back to the Life Shortest Stories Contest, the winners of which were published in 1916. As luck would have it, we have a little extra space this month, so I’m including both third-prize winners this month: “Business and Ethics” by Canadian author and editor Redfield Ingalls, and “Her Memory” by Dwight M. Wiley. They’re quite different stories, but they both speak to the longing inherent in the human condition, whether in its disordered and greedy forms or its proper — though sometimes thwarted — operation.

Bruce Holland Rogers is unfortunately unable to contribute this issue, but he’s hoping to be back next month.

A special thanks to R.W. Ware for his illustrations this month.

Please enjoy the stories, and remember, comments are like gold to authors. Then again, gold is like gold, too, and tipping is appreciated.