“I’m Radok,” he said to her when everyone was gone, and steam hissed gently from his vents.

Sandra hadn’t noticed him in the audience. How could she have? They came every night and sat at their tables with rattles and creaks. Gray-blue visages bathed in the golden light from Outside. Here a steel leg crossed over a many-jointed knee, there a dozen long fingers laced together in a steeple. Seated, they stilled themselves like Victorian gentlemen posing for monochrome immortality. It made her want to jump up and scream, but she’d tried that before to little avail.

Nor did this Radok stir when she began to play. None of them did. As her hands found note after note on the scuffed keyboard, intimately familiar from a thousand nights since the End and three thousand before, as the damp-warped strings rasped out a melody that carried her to the faraway lands of memory, they didn’t so much as breathe.

A creak — on the shoulder of one, a vent closed. A hum — someone’s exhaust fans spun up.

Too soon, her song was over, all of it spent and done. Sandra kept her fingers sunk into the piano as the last of the sound reverberated and faded into silence. She sat still while her audience rose to their feet with a susurrus of clangs and tinkles, and shuffled to the exit. The airlock sucked them through to Outside one by one — hiss, plop. Hiss, plop.

When Sandra rose from the piano, he spoke from behind her, his voice cold and smooth. “Excuse me. I’m Radok.”

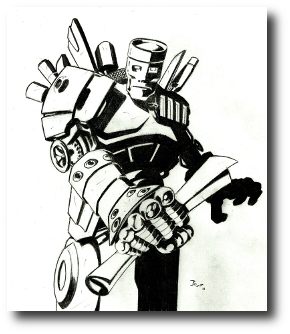

She whirled on him, heart hammering. Tall, this one, thick iron limbs riveted with bolts an inch in diameter.

Anger born of surprise gave her voice a hard edge. “I’ve played for tonight. One song, as agreed.”

“I ask a favor. Will you play this for me?” He reached into a cavity in his chest and drew out a sheet of paper.

Sandra took it. A score! Sol major, neatly printed. “Where did you find this?”

“In the ruins of Kalata.”

“You’re lying.” The sheet was pristine, unmarked. It had no smell of sulfur on it — it hadn’t seen Outside. Then she played the first notes in her mind, and she knew. “You wrote this!”

A blur, and Radok loomed over her, sharp angles and corrugated planes. Steam stung Sandra’s eyes, but she didn’t flinch. Surely he wouldn’t hurt her — she was precious to them, one of a kind.

“Play. Now.”

“Play it yourself.” Sandra shoved the sheet at his chest.

Radok sprang back, fast, joints screeching. He watched the piece of paper seesaw to the floor. “I tried. It’s not the same.”

Sandra turned away from him. Walked to the window and looked out into the light, the golden light that drenched Outside like bleach, leaving but a few dark shadows here and there. Tall, the skeleton of a tower. A row of humps in the distance — the domes of the city market. Home.

“I’ll play,” she said, “if you take me Outside.”

With a series of gentle creaks, Radok joined her at the window. “We thought everything would be easier.”

Sandra shivered. She’d never gotten one of them to speak about the End before — all they’d been willing to discuss had been her food and her medicine, and the demand that she play each night. “Well, isn’t everything easier?” She spread her arms wide. “Orderly. Simple.”

“Yes,” he said, “and silent.”

“Then let me out.” She shouted the words — “Let me out!” — and beat on his chest with her fists.

Pain, sharp. And he surged toward her and threw her at the window. Sandra only had time to think — one of a kind indeed — and her head hit glass. Her vision spun.

“No,” he said.

No.

Sandra flushed, not in anger but in shame. For a fleeting moment, just as that simple “No” left Radok’s cast-iron mouth, what she’d felt had been relief. That she needn’t see what they’d made of her world. Needn’t touch and smell what remained. That she might stay in her prison for a while longer.

Sandra hated him just then. She could have thrown herself at him again and been killed, and not regretted it. But a thought occurred to her. Something better than a pointless death.

“I’ll play.”

Radok stepped away from her. “Will you?”

She smiled at him. “Yes.”

Sandra retrieved his sheet of music and settled at the piano. As her eyes roved over the notes he’d written, she tried to ignore the pain in her hands where she’d struck him, the ache in her biceps where he’d held her. And she played. Note after note, as he’d written it. She poured all her anger out through her fingertips, all her pity too, and all her loss. Once through the score she played, then again, a different way. Then once again, striving for her utmost, honest best.

Radok stood behind her, unmoving, silent. When she finished, he spoke with a note of wonderment in his voice, and with a quiet pain. “It’s not music. It’s not music, is it?”

“No,” she said. “It isn’t.”

“But why?”

Sandra rose. She turned away from the piano and walked toward the window where the light of Outside had begun to fade into darkness. She stared out at the shapes that loomed beyond, dark, silent, unmoving, and wondered if she was the last of her kind.

She didn’t pull away when Radok joined her and clanked his fingertips against the glass. He didn’t repeat his question. “I’ll try again,” was all he said, quiet, sure.

Together, they stood there and watched Outside sink into night, while somewhere in Sandra’s head a song played. It was tomorrow’s song, a song that waited for her. Waited to carry her to the faraway lands of memory. Her fingers stirred to its beat.

Just then, listening to the even hiss of steam from Radok’s joints, the Outside within was enough for her.